Teacher-Led Tooling for the Adoption and Improvement of AI Models

December 2, 2025

By Simon Woodhead, Chief Data Scientist & Co-Founder at Eedi

AI systems are advancing rapidly, but in education, progress is gated by something deeper than raw model performance: trust. Teachers and students do not interact with models in the abstract. They interact with them in contexts filled with constraints, expectations, and responsibilities. An AI education tool is only useful if its users feel confident and empowered while using it.

This article outlines how Eedi approaches AI adoption within schools, why we continue to collect real-world human data (in a synthetic-data era), and how our human-in-the-loop question-generation system, AnSearch, helps teachers create high-quality formative assessment while generating valuable training signals for the next generation of models.

Trust Is Not a ‘Nice-to-Have’

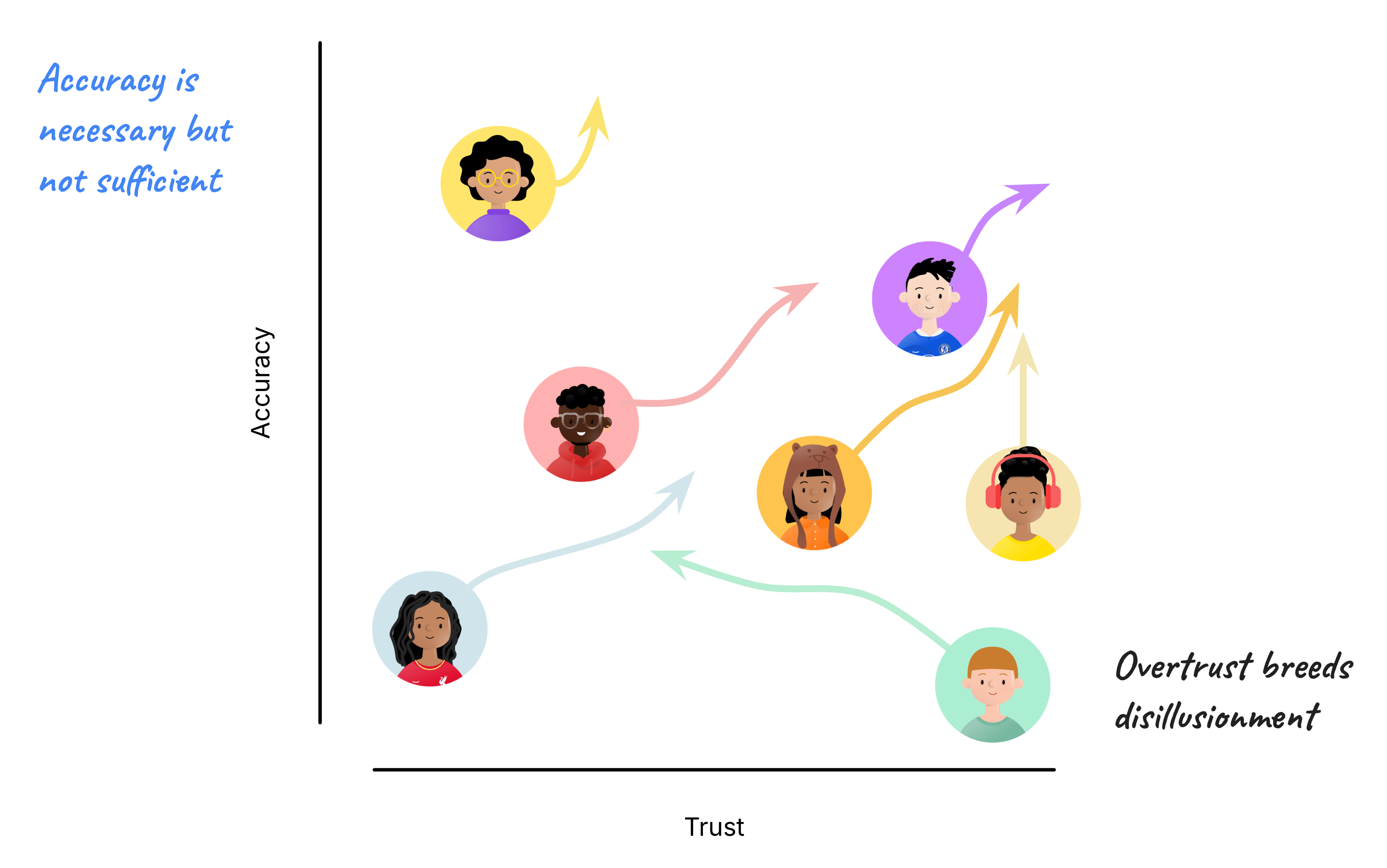

It’s tempting to imagine a straight progression: models become more accurate → users trust them more → adoption grows.

Unfortunately, trust does not behave that neatly.

Teachers vary enormously in both their enthusiasm for AI and their tolerance for model error. Some will eagerly try every new tool that appears. Others remain deeply skeptical, even when performance improves. And neither group is wrong - each is simply responding to their experience.

Accuracy is necessary, but not sufficient.

A single surprising hallucination can permanently poison a teacher’s perception of the system. Conversely, too much early enthusiasm can collapse into disillusionment when the model reveals its weaknesses.

What matters is not pushing everyone to trust AI, but creating tools that allow trust to grow proportionally and sustainably as models improve. That requires design choices that keep users in control.

Why We Still Collect Real Tutoring Data

A common question today is: Why collect more human dialogues? Can’t an LLM just simulate student behaviour?

The short answer: not yet, and not to the standard required for learning research.

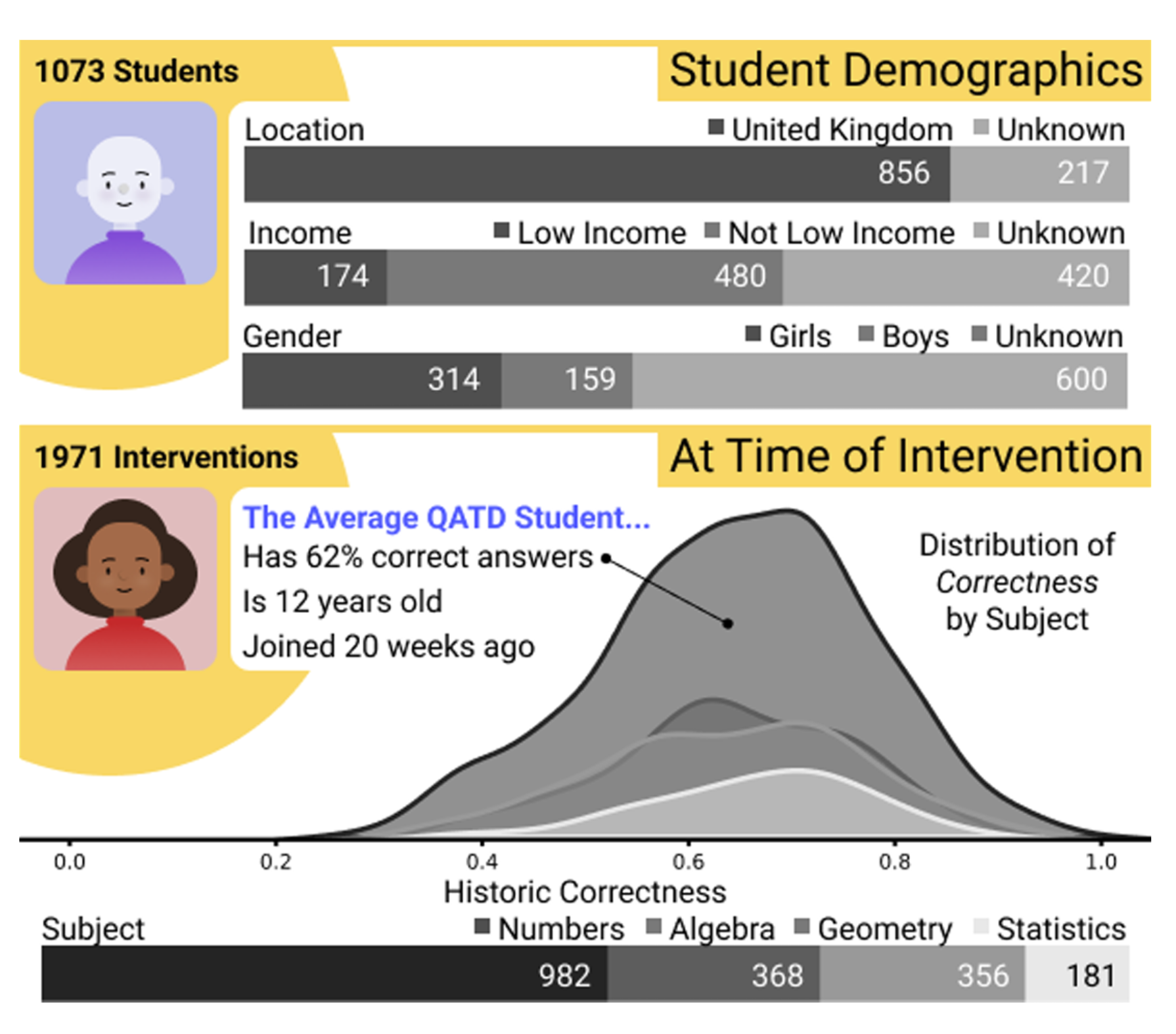

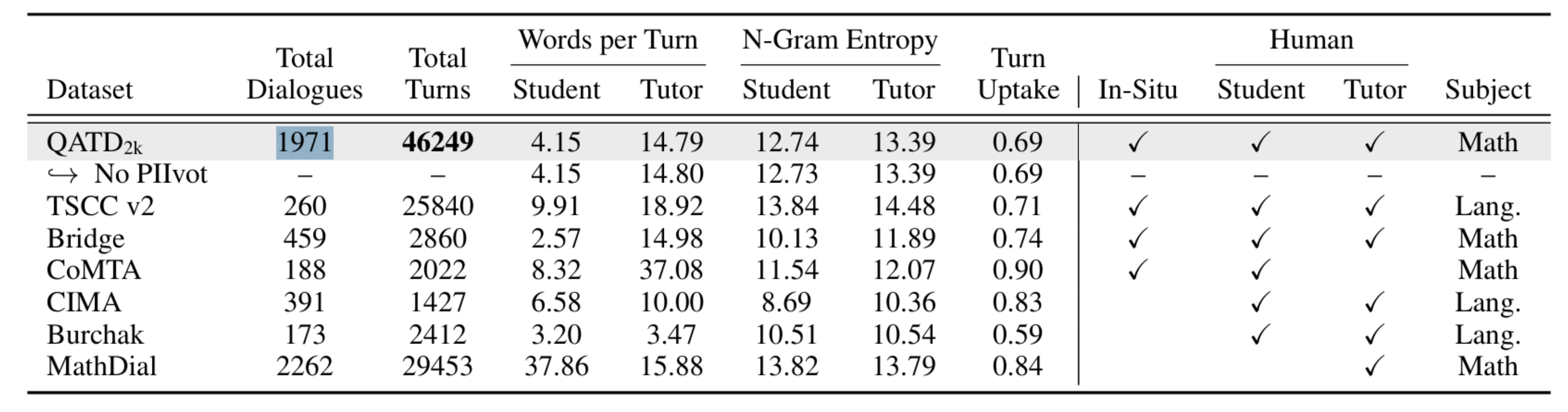

Source: Zent et al. 2025

Source: Zent et al. 2025

We recently released QATD2k, a dataset of 1,971 authentic tutoring dialogues between human tutors and human students. When compared against datasets containing AI-generated students, a striking pattern emerges:

- AI “students” produce messages 5-10x longer

- Their responses include structured reasoning that no real student offers

- Their mistakes resemble teachers pretending to be students rather than genuine misconceptions

- They lack the brevity, hesitation, and noise characteristic of real learners

This difference matters. Education research is built not on correct answers but on misconceptions. Real student misconceptions arise from developmental, experiential, and curricular factors that models do not yet reproduce convincingly.

Synthetic data may be useful augmentation, but it cannot replace real-world human data, especially for modelling learning, difficulty, and misconception patterns.

This is why Eedi has spent a decade releasing open datasets, hosting competitions, and supporting the learning engineering community. Good data accelerates the entire field.

A Decade of Formative Assessment at Scale

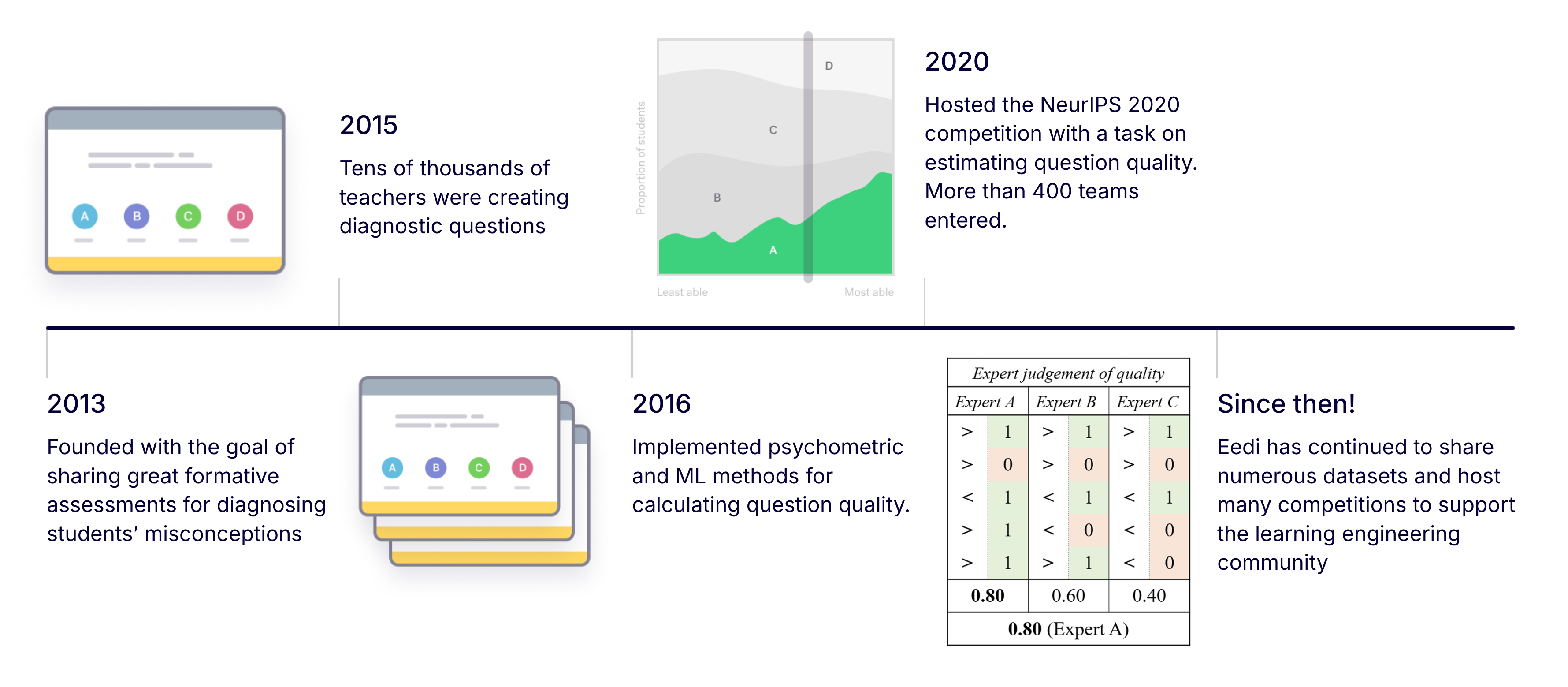

Eedi began in 2013 with a simple idea: formative assessment (diagnosing student misunderstandings during teaching) should be easy, scalable, and grounded in evidence.

Originally, we invited teachers across the UK to contribute diagnostic questions. Tens of thousands were created. But quantity introduced a new challenge: quality. Psychometrics can be used to evaluate question quality, but it requires large-scale student responses, and careful modelling. So we explored using ML systems to estimate question quality directly.

This eventually led us to host research competitions (including at NeurIPS 2020) and publish well-used datasets, helping the wider community advance models for question difficulty, misconception detection, and knowledge tracing.

Generative AI opened a new frontier: could we help teachers create even better questions, with less effort, while retaining the human judgment necessary for trust?

Introducing AnSearch: Human-in-the-Loop AI for Question Design

Teachers today can ask an LLM: “Generate ten questions on algebra for Year 8.”

But this is not enough for diagnostic assessment. We need:

- Reliable question structure

- Distractors aligned to real misconceptions

- Transparency into why options are generated

- Consistency across large banks of items

- Opportunities for teachers to refine and override the AI

AnSearch was designed with these goals in mind.

How AnSearch Works

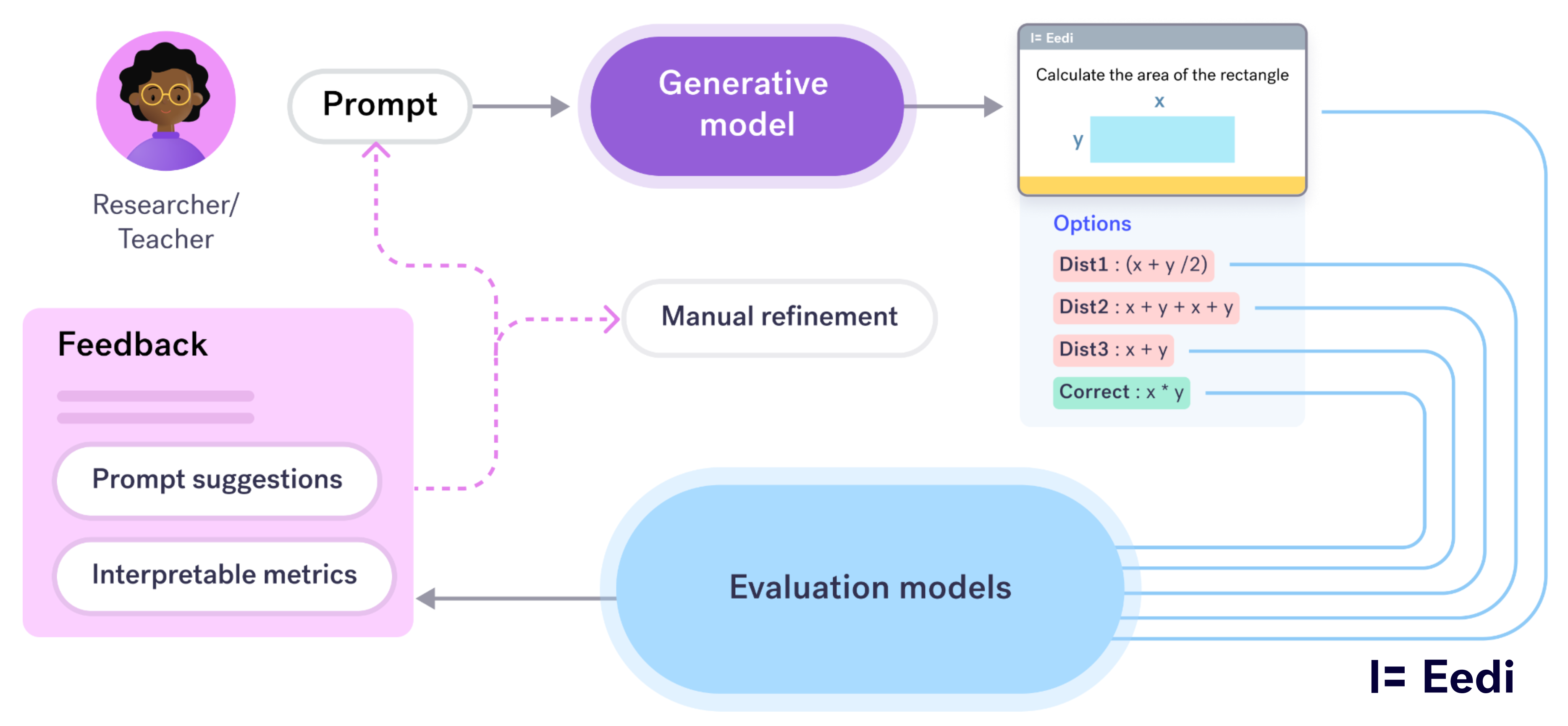

The workflow has three components:

- Teacher prompt: Teachers specify topic, difficulty, constraints, and year group. Without the year group, models often stray too easy or too complex.

- Generative model output:

- A draft question

- A correct answer

- Several distractors (each tied to a misconception)

- Explanations for each option

- Evaluation models: We run the generated content through evaluators that assess

- Style consistency with human-authored items

- Whether distractors are plausible

- How likely each distractor is to be chosen

- Whether misconceptions are well-formed

Teachers then receive feedback and prompt suggestions to adjust or regenerate content.

At this point, the teacher can choose whether to act on the feedback, e.g. prompting the generative model to change one of the distractors, or exit the loop and make some final manual fixes.

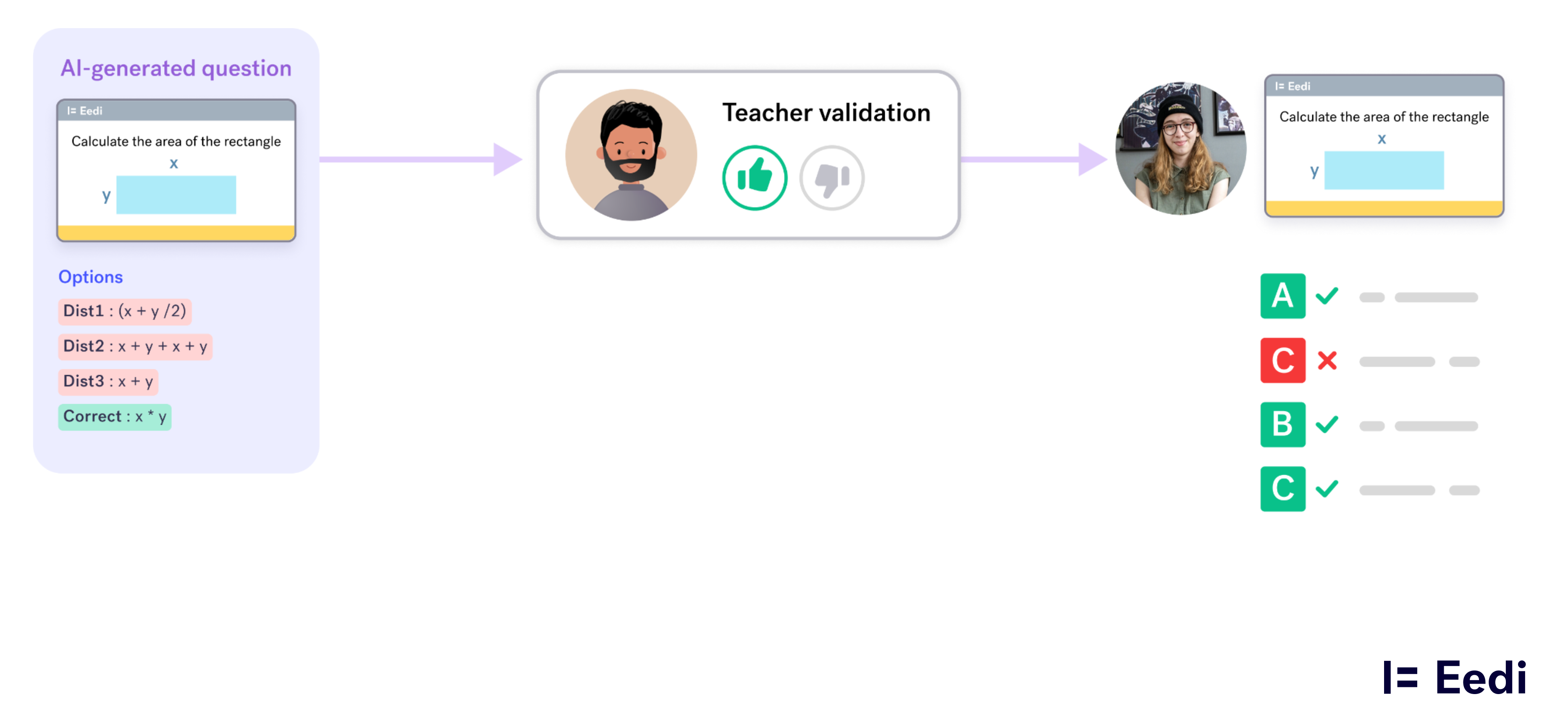

Every question undergoes human validation, being checked by another content author, before it is shown to students. This protects students and also protects teacher trust: the AI accelerates work, but the teacher remains the authority.

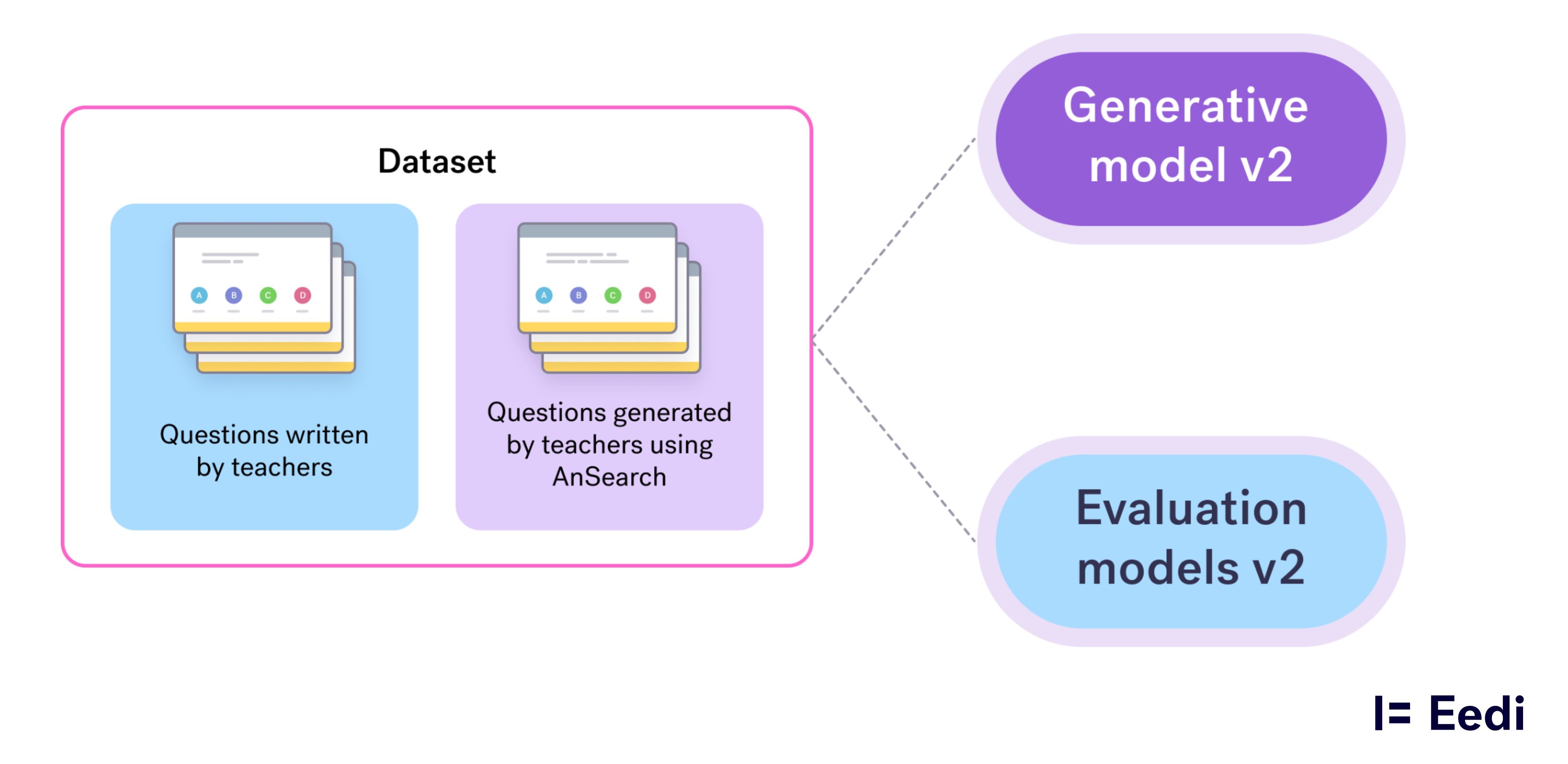

So we now have two datasets:

- Human-authored questions with responses

- AI-assisted questions with full interaction traces

These datasets provide a great source for training improved generative models and better evaluation models. Because we capture every iteration, rejection, and manual correction, we obtain far more granular insights than final outcomes alone could ever provide.

What Teachers Told Us: Early Findings

Evaluation metrics were not trusted

Early versions relied too heavily on LLM judges, which tend to be overly positive about their own outputs. Teachers quickly learned to ignore these scores, and once you lose trust it is difficult to regain. LLM judges have a role, but are best used within an ecosystem that includes human benchmarking and more structured metrics.

Distractors were often useful but rarely perfect

Most items required editing of at least one distractor. Some teachers framed this as a failure; whereas we thought of this as quite a positive outcome – AnSearch was correct most of the time, and helped “fill in the gaps” when given a nudge.

But perception matters: if teachers expect perfection, even small edits feel like shortcomings. Setting expectations correctly is crucial.

The system could feel “buggy”

Requests such as “regenerate only the third distractor” occasionally produced unexpected behaviour. This is not a coding bug – it’s inherent to the stochastic nature of LLMs.

But unless we communicate this, users interpret stochasticity as instability.

Manual editing is essential

The strongest feedback of all: “If I couldn’t manually edit the question, I would have given up.”

This affirms that human agency is not an optional feature; it is the core of trust-building.

Misconceptions: A Cautionary Example

One generated distractor for a question with a correct answer of 126 was… 126.

The model then speculated about a “misconception” the student might have used to arrive at this “incorrect” answer.

This reflects a deeper issue: LLMs do not understand mathematical validity in the way teachers do. They imitate patterns of text rather than reason symbolically.

There is promising research exploring hybrid models - symbolic engines combined with LLMs - and specialised models that generate misconceptions more reliably. But the example underscores why human review remains essential.

Collecting a Diversity of Teacher Opinions

Teachers differ in style, interpretation, and expectation. If we design only for the most confident or tech-forward teachers, we lose the majority.

By gathering data on:

- Which distractors teachers keep

- Which they discard

- Which misconceptions they believe are valid

- How they rewrite explanations

- How they interpret student thinking

…we gather not only preference data, but pedagogical diversity. This is foundational for building models that reflect real classrooms rather than idealised ones.

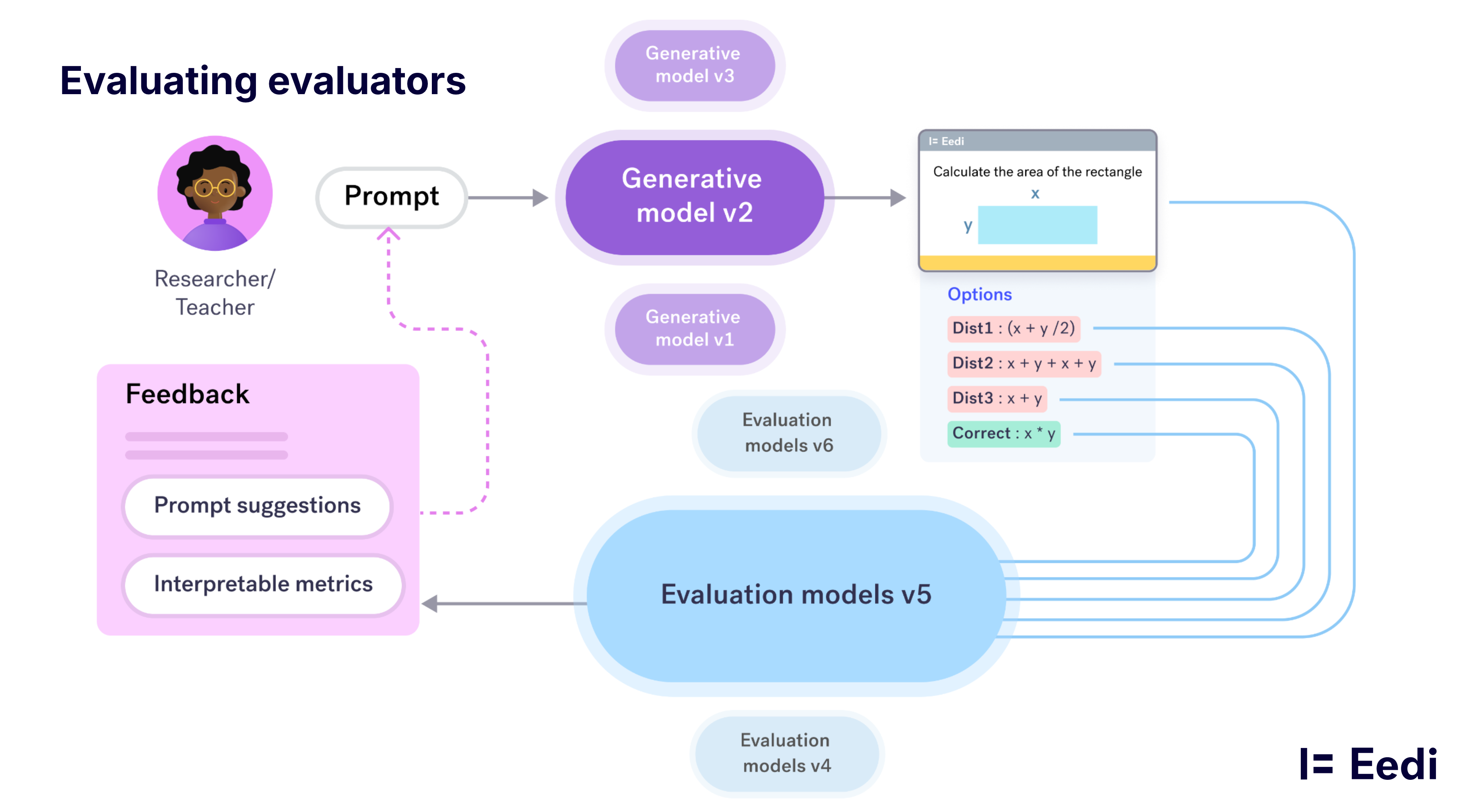

What’s Next: Evaluating Evaluators

The future is not just better generative models — it’s better evaluators.

We envision modular, agentic systems where:

- Multiple generative models compete

- Multiple evaluators assess their outputs

- Benchmarks are built into the creation pipeline

- Researchers can plug in new components

- Communities can run competitions on these modular systems

Think of it as creating a platform where innovation happens inside the workflow rather than around it.

The Future of Formative Assessment

Multiple-choice questions will continue to exist because they are fast, scalable, and practical for classroom use. But they are only one piece of a broader diagnostic ecosystem that will combine:

- Quick MCQ checks

- Conversational diagnostics

- Misconception-specific feedback

- Classroom response scanning

- Human-authored and AI-assisted content creation

LLMs are powerful tools, but they are not (and should not be) autonomous actors. Their greatest value emerges when they augment teacher expertise, not bypass it.

The real opportunity is not “AI tutors replacing teachers,” but teacher-in-the-loop AI, where human judgment improves model outputs and where the interaction between teachers and AI generates the data needed to train the systems of the future.