Education as Medicine

March 12, 2025

By Vassili Philippov

The current state of education as a science reminds me where the medicine was slightly less than a hundred years ago. On a verge of converting from guesswork to a proper science. But for now many educational practices are still rooted in tradition and intuition rather than evidence. It’s as if we’re still relying on leeches and bloodletting to cure educational ills.

What if Schools Worked Like 19th-Century Hospitals?

Imagine walking into a hospital in the early 1800s. Doctors rely on intuition, tradition, and personal experience. Treatments are based on what feels right, not what works.

A fever? Bloodletting.

A headache? Leeches.

A cough? Mercury.

There’s no controlled testing, large-scale studies, or standard for proof. Medicine is built on anecdotes, authority, and outdated beliefs1.

Now, imagine walking into a school today. Any similarities?

How do we know what works in education?

Because a famous professor says so? Because a best-selling book claims it does? Because it “feels right” to teachers and parents?

In many ways, education is stuck in its pre-scientific era—where intuition beats data, and strong beliefs outlast strong evidence.

But soon enough, education will have its “medical revolution”, it is actually happening now (kind of…).

Do Doctors Really Need to Wash Their Hands?

Vienna, 1840s. A Hungarian doctor, Ignaz Semmelweis, notices something strange. Women in hospitals are dying from puerperal fever (childbed fever), with a mortality rate of 13% to 18% (sometimes even exceeding 30%). But at the same time, the death rate when giving birth at home is just 1%.

At some point, Semmelweis’s colleague, Professor Kolletschka, dies after accidentally pricking his finger with a student’s scalpel during an autopsy. The autopsy reveals symptoms remarkably similar to those of women dying from puerperal fever.

Semmelweis realizes that doctors were conducting autopsies in the morgue and then directly attending to women in labor in the maternity ward. “Cadaveric particles” (what we would now call pathogens) from the morgue were being transmitted by the doctors’ hands to the women in labor, causing puerperal fever.

So Semmelweis suggests a simple solution: doctors should wash their hands with a chlorinated lime solution before delivering babies. After some fight and struggle, he institutes a mandatory policy in the hospital, and death rates drop by 90%.

But the result for Semmelweis himself was dramatic. His assistantship at the clinic was not renewed. He had to move from Vienna to Hungary and find a new job. For over 10 years, he published articles and shared his knowledge. He even wrote a book, Die Aetiologie, der Begriff und die Prophylaxis des Kindbettfiebers (The Etiology, Concept, and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever).

To cut the story short, he died in an asylum at the age of 47, ridiculed by his professional peers. His ideas and evidence-based research challenged the status quo. They implied that doctors themselves were the cause of death. Didn’t feel too comfortable. His research was ignored for decades.

We don’t know how many women died because of that. Semmelweis’s story shows how evidence can be ignored when it challenges entrenched beliefs — a pattern education repeats today.

The Reading Wars: Why Are We Still Ignoring the Science?

Imagine you’re teaching a child to read English. You have two choices:

- Teach them how letters and sounds work together so they can decode any word they encounter.

- Have them memorize whole words and guess unfamiliar ones using pictures and context clues.

Which approach sounds more reliable? Now, imagine you’re designing a national education system. Which method would you choose?

For centuries, the answer was clear. Phonics—teaching children to connect letters with sounds—has been around since at least the 1600s2 , and it worked. Generations of children learned to read by breaking down words into their building blocks.

Then came the 1800s, and with it, Horace Mann3. Mann—widely regarded as the father of American education—believed sounding out words distracted children from their meaning. Instead, he argued, children should learn to recognize words as whole units, just as they recognize faces. By the early 1900s, phonics had been replaced in most American schools by a look-say method, later known as whole language4.

By the 1950s, the results were clear. Kids weren’t learning to read. In 1955, Rudolf Flesch, a literacy expert, published Why Johnny Can’t Read5, a critique of the American education system.

His argument was simple:

- Children weren’t being taught phonics.

- Without phonics, they couldn’t decode words.

- Without decoding, they weren’t actually reading.

Flesch was backed up with research. Third graders couldn’t even recognize 90% of the words they spoke daily because they had never been taught to sound them out6. His book became a bestseller. The debate exploded into what we now call the “reading wars.”

Surely, this was the moment phonics would make a comeback, right? Nope.

Despite the growing evidence, whole language refused to die. Because it felt right. It was progressive. It treated children as natural learners. It made classrooms feel less rigid and more creative. Teachers embraced it. Textbook publishers profited from it.

- In 1980, 44% of U.S. students performed below basic literacy levels7.

- By 2000, the National Reading Panel confirmed that explicit phonics instruction was essential for strong literacy skills.

- By 2022, despite decades of evidence, only 35% of American students read proficiently8.

While some districts have embraced phonics, national adoption remains inconsistent.

You may wonder if Mr. Flesch died in an asylum too. No parallels here, fortunately—he died at age 75 in New York. But phonics is still not systematically taught in the U.S.

In the 1990s, with reading scores stagnating, a new approach emerged: balanced literacy. It was meant to be a blend of whole language and phonics, a compromise that sounded reasonable in theory. Schools claimed they were using evidence-based instruction, but in practice, they continue the same ineffective strategies—relying on guessing, context clues, and memorization instead of teaching students to decode words systematically.

The Bloodletting of Education

Bloodletting was standard practice for centuries. Doctors swore by it. Patients believed in it. The problem? It didn’t work.

In education, we have our own “bloodletting” practices—methods that are widely used but have little to no evidence:

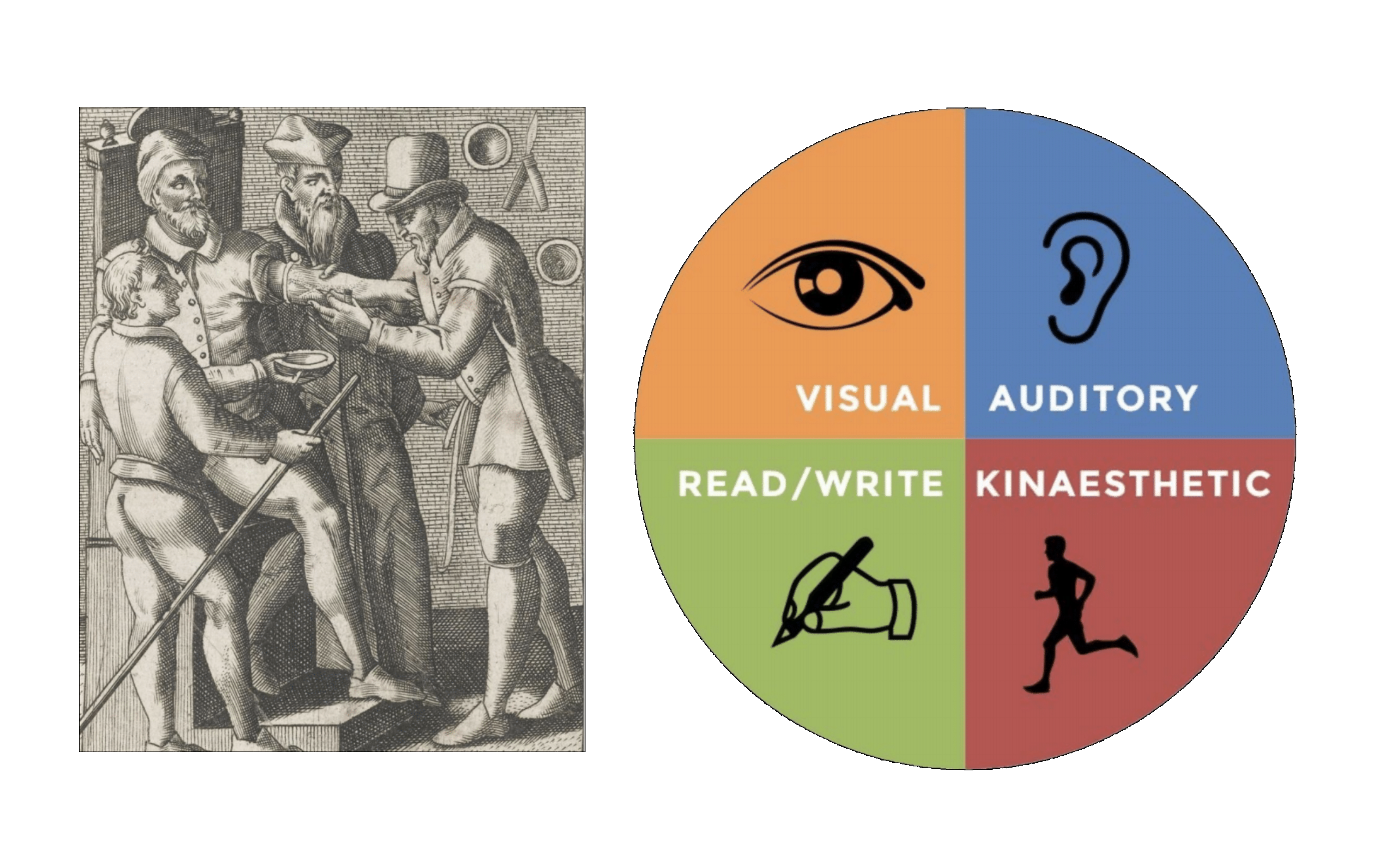

- Learning styles – No scientific basis, yet schools still test students for their “learning type”9.

- Brain training games – Marketed as IQ boosters, but studies show minimal impact10.

- Right-brain vs. left-brain learning – A complete myth, yet still in teaching materials11.

- Discovery learning (where students explore concepts with minimal guidance) over direct instruction – sounds appealing, but research favors structured teaching12.

So why do they persist?

Just like bloodletting, they feel right. Changing course means admitting mistakes. Rejecting them means undoing years of training and policy.

In medicine, we don’t accept treatments without proof. Why do we accept it in education?

But studying education is harder than studying medicine

If medicine solved this problem, why didn’t education? Because education is much harder to study.

- No Placebo – we can test a drug against a fake pill in medicine. In education, there’s no “fake lesson.”

- Ethics – You can’t randomly assign some kids to a bad teaching method for the sake of research.

- Long-Term Effects – Learning impacts years of life. Measuring short-term results is easy. Measuring lifelong outcomes is hard.

- Classroom Complexity – Every student, every school and every teacher are different. No two classrooms are the same.

Although Progress Is unavoidable

Medicine changed when it embraced rigorous testing.

- RCTs (Randomised Controlled Trials) became standard.

- Doctors stopped relying on tradition.

- Hospitals demanded evidence before adopting treatments.

The result? A revolution in healthcare. Life expectancy doubled. Treatments became safer and more effective.

Education could follow the same path and increase humanity’s chance of survival.

But it needs:

- More high-quality RCTs in learning science.

- Stronger evidence standards before adopting new policies.

- A culture shift—intuition isn’t enough.

Education now is where medicine was in 1960-1970. And the science-based progress is inevitable. The number of RCT studies is growing across the world13. However, a crucial gap exists between clear scientific evidence and policy change. The phonics case is just one of many.

In 10-15 years, we’ll look back with astonishment. How did we ever trust intuition over proof?

References

-

Porter, R. (1997) The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present

-

Keele University (n.d.) A Guide for the Childe and Youth - Special Collections Showcase

-

Mann (1848) Twelfth Annual Report of the Secretary of the Board of Education

-

Stephen Parker (2021) A Brief History of Reading Instruction

-

Why Johnny Can’t Read—And What You Can Do About It by Rudolf Flesch

-

Time 1955 Education: Why Johnny Can’t Read

-

National Center for Education Statistics (2022) NAEP Reading: Reading Results

-

Pashler et al. (2008) Learning styles: Concepts and evidence

-

Simons et al. (2016) Do “Brain-Training” Programs Work?

-

Nielsen et al. (2013) An Evaluation of the Left-Brain vs. Right-Brain Hypothesis with Resting State Functional Connectivity Magnetic Resonance Imaging

-

Alfieri et al. (2011) Does discovery-based instruction enhance learning?

-

Connolly et al. (2018) Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in education research – methodological debates, questions, challenges